EARL BISS

Master of American Impressionism

Earl Biss was the primary catalyst for a movement in the art world that saw Native American art transition from anthropology museums to art museums - literally from folk art to fine art. The wave Earl Biss and his Native colleagues started in the 1960s and 70s is still spreading, as indigenous art and artists from Asia, Africa and Latin America now assume their rightful places on the world stage.

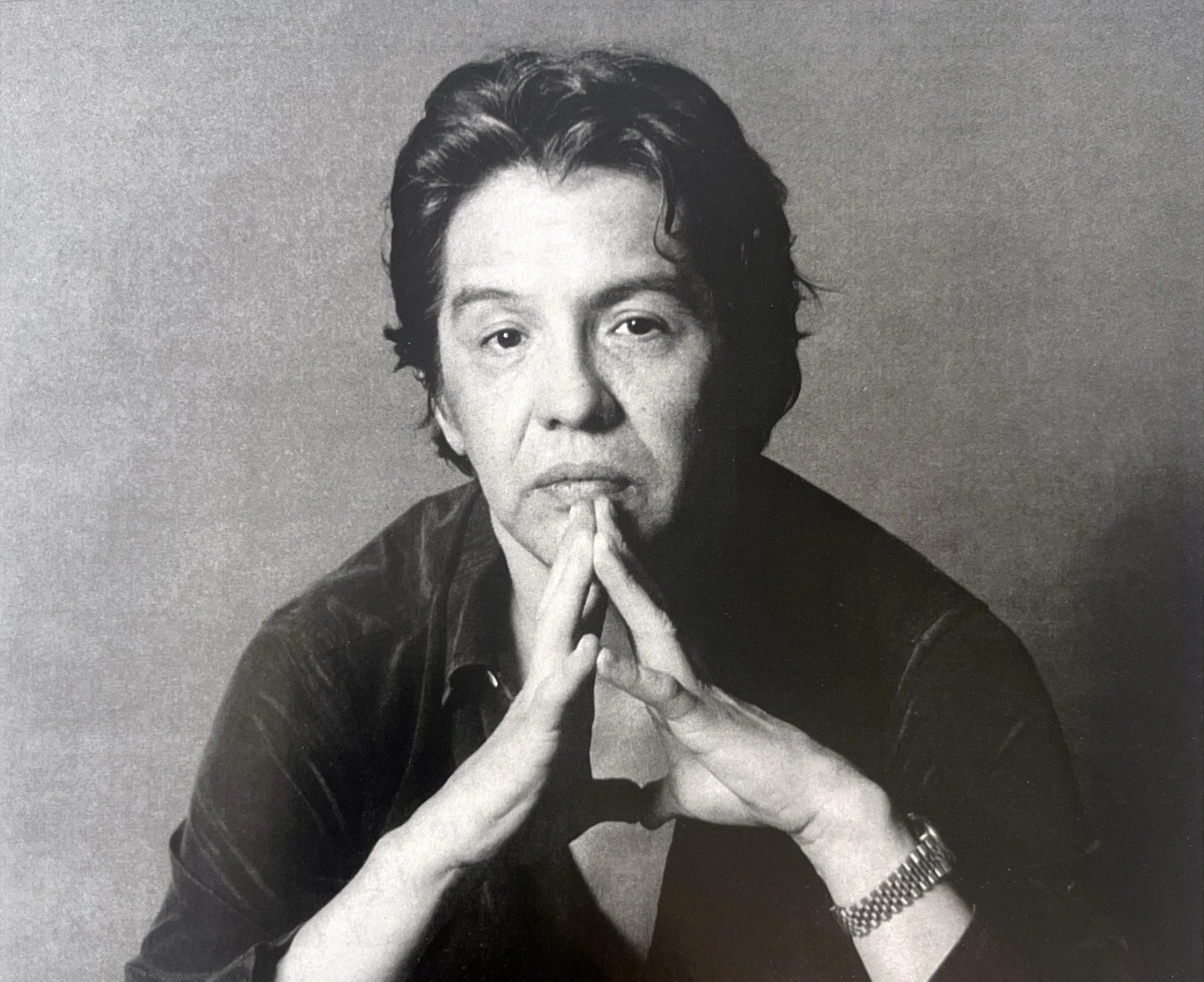

EARL BISS (1947-1998)

Earl Biss was a man driven by visions and demons. He was brilliant, charming, sometimes violent and, as his friend Hunter S. Thompson affectionately said, 'crazy as five loons.' He carried the power, and the trauma, of his Crow Indian heritage. Like his shaman ancestors, Earl was a shape shifter, moving between the worlds of Native and white, high society and the street, art and the underworld. His collectors ranged from a president of the United States to a president of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club.

A central figure during the 1960s among a group of artists at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, including Fritz Scholder, T.C. Cannon, and Kevin Red Star, Biss contributed to changing the face of Indian and Southwest Art. A classically trained artist, he was exposed to Abstract Expressionism while studying under Fritz Scholder. Incorporating this style into his work and using it as an emotional outlet, Biss presented a contemporary Native American perspective, portraying in a modern visual language the Indian living in the modern world.

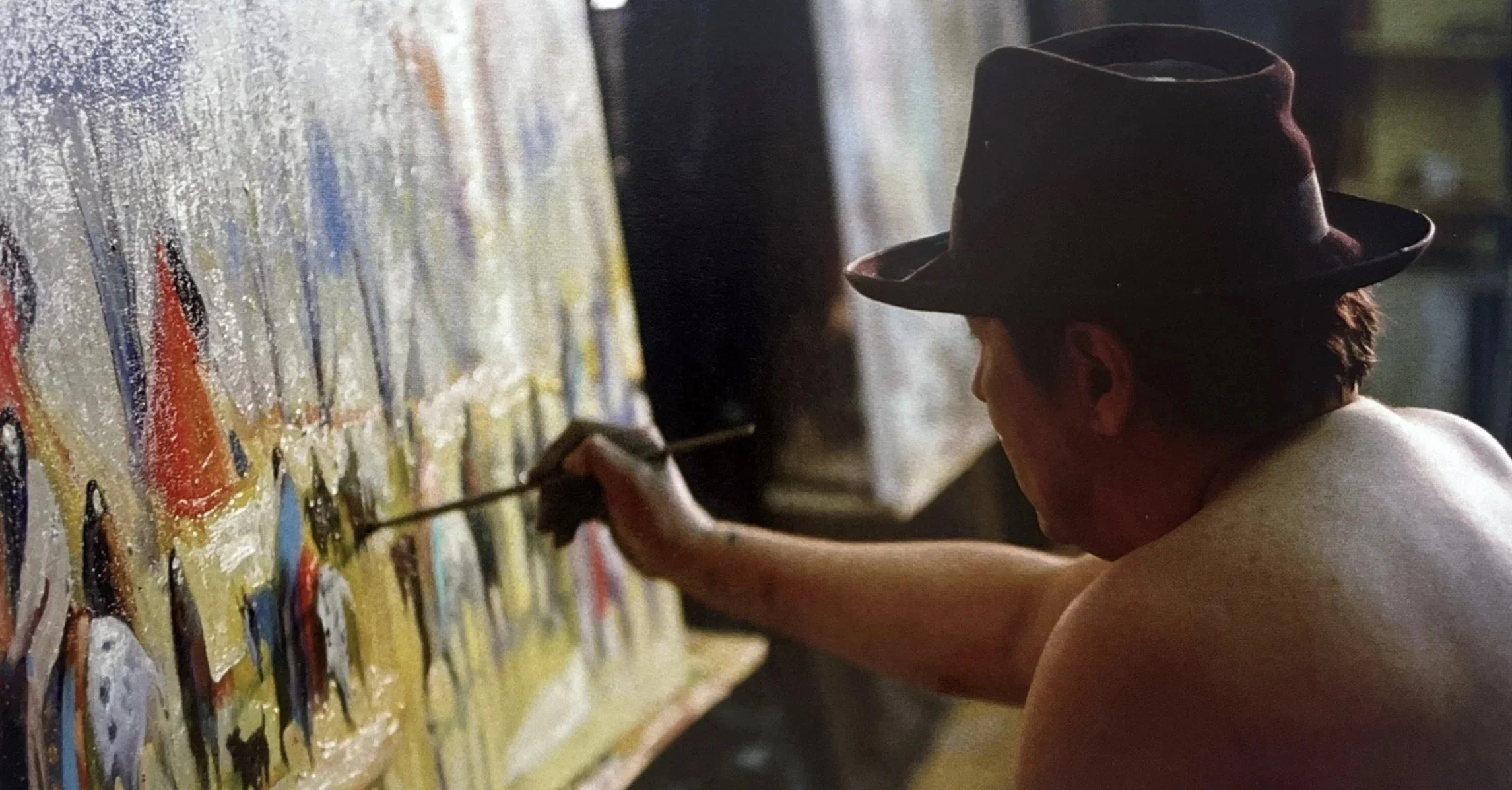

Biss was one of the greatest masters of the medium of oil paint in history and one of the greatest colorists. He was also the primary catalyst of the movement that saw works created by Native Americans transition from 'folk art' to fine art, and move from anthropology museums to major art museums. He called his technique moving paint,' and often worked in maniacal bursts of up to seven days and nights straight. He regularly painted with both hands on separate canvases using different palettes, and wielded tools from sable brushes to torn chunks of cardboard, brooms and bare feet. Fueled by drugs, alcohol and a profusion of lovers, he could produce as many as 60 canvases in those marathon sessions.

Earl was married at least eight times and arrested far more times. There were no boundaries in his world, and he was compelled to break rules, shatter relationships and subvert his own success, just as he was compelled to push the edges with his art. A self-described mongrel alcohol orphan,' he made art because he couldn't not make art. And because making art helped heal the trauma of his own life and, he hoped, that of the world Earl Biss grieved for his alcoholic mother, his friends lost to violence and substances, and the landscapes and lifestyles taken from his people. He poured his pain and grief, along with his hope and love, into his canvases. And though he died too young, he left behind a profound and lasting beauty.

EARL BISS: A JOURNEY THROUGH ART & SPIRIT

A TIMELINE OF FIRE, PAINT, AND LEGACY

Young Earl: Raised by the Prairie Sky

(1947–1965)

Earl Vernon Biss Jr. was born on September 29, 1947, in Renton, Washington. His father, Earl Biss Sr., was the son of an Anglo father and a Chippewa mother. His mother, Dorothy Shane, was Crow, with Cheyenne and French lineage. Because the Crow are matrilocal, the family returned to the Crow Reservation in southeastern Montana.

Biss was a descendant of White Man Runs Him, the Crow scout who rode with Custer. While other boys rode bikes, he recovered from rheumatic fever with a paintbrush in hand. He danced at powwows, made his own regalia, and kept it close—ready to honor the land wherever he stood. “I am not concerned with capturing the outward image of nature,” he said, “but rather those powers or forces of nature… a concept of reality drawn from spontaneous abstractions.”

He was first named Meadow Lark Boy, a name of lightness and song; later, upon his first marriage, he became Spotted Horse—honoring the warriors of his ancestry who rode the wind across the plains; and in time, the Crow bestowed upon him a final name: Ghost Who Walks Among His People—a tribute to the spectral presence of his ancestors made visible through paint, and to the power of his art to return home even when he did not.

Where Color Broke Loose: IAIA & SFAI

(1965–1971)

In 1965, Biss enrolled at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe. There, his work exploded in color and scale under the influence of Fritz Scholder, Charles Loloma, and Allan Houser. He apprenticed with John Chamberlain, and worked alongside Paolo Soleri, helping construct the IAIA amphitheater.

The next year, he won one of ten national scholarships to the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), where he studied among future giants. “It was a golden era,” Biss said, “which one day will be recognized as an important movement in American art.”

He painted like a man possessed: 7-foot oils, hard-edged flags emblazoned with protest, glowing color fields with warriors pulled from abstraction. His “Thunder Egg” series—a suite of circular, glazed canvases with more than 30 layers each—became a hallmark of his non-objective mastery. These evolved into the mythic “Night Riders” paintings. When one of these sold from a back room near the bathroom, Biss said, “They were already there. I just let them out.”

He painted in London, Amsterdam, Rome, and Majorca, devouring Turner, Rembrandt, and the stormy skies of the Old World. At home, he was already a comet across the canvas.

The Movement: After IAIA & the Rise of

Contemporary Native American Art

(1970s)

Back in Santa Fe, Biss and his fellow IAIA alumni—Kevin Red Star, T.C. Cannon, Doug Hyde—rented studios and formed an unlikely but historic scene. Visitors included Dan Namingha, Bob Haozous, and Harry Fonseca. “Earl was the catalyst, like the agitator in a washing machine,” said Red Star. Their energy gave rise to what became known as Contemporary Southwest Art.

In 1975, Biss showed at Elaine Horwitch Gallery in Scottsdale. He arrived barefoot, in a new Saks Fifth Avenue suit with a bear claw necklace and no shirt. He sold out the entire show. The legend was born.

Biss painted up to 40 canvases at once, working for 48–72 hours straight in the rhythm of a Plains Sundance—“a sacrifice of flesh and spirit,” he’d say. As his fame rose, so did the wildness. He lived large, loved deeply, married eight times, and never stopped painting.

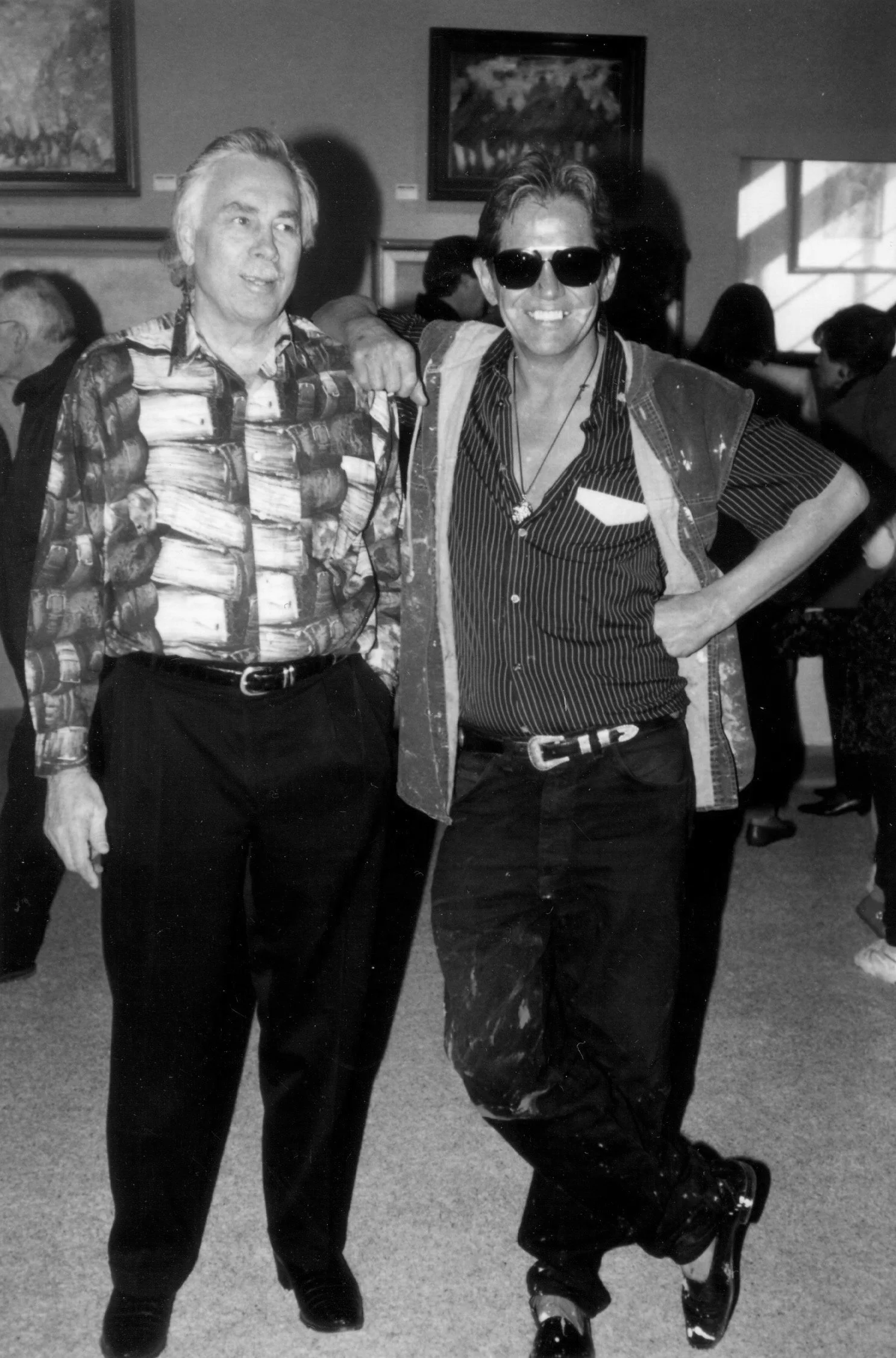

A Wild Genius Meets His Match:

Earl Biss & Paul Zueger

(1978–1998)

Earl Biss was a visionary painter and a force of nature—brilliant, unpredictable, and often self-destructive. When Denver art dealer Paul Zueger took a chance on him, it sparked one of the most volatile and iconic partnerships in contemporary Western art.

Though Biss had moved from gallery to gallery, everything changed when he met Zueger. Through Zueger’s network of galleries—Gallery One in Denver, Aspen Grove, Gateway Gallery in Vail, C. Anthony in Beaver Creek, and Galerie Züger in Santa Fe—Biss found long-term stability and serious representation.

He kept studios in Red Lodge, Santa Fe, and Colorado, producing relentlessly. Every serigraph and oil was supervised or touched by his hand. “If the artist doesn’t paint in oils, he isn’t a real artist,” he often said. He was a purist and a mystic, a perfectionist and a provocateur.

Through Zueger’s backing, Biss had the infrastructure to match his vision—and collectors followed. During his lifetime, his work sold from $5,000 to $40,000, and entered major collections across the U.S. and abroad. Since his passing, the value of his paintings have multiplied several times over. Zueger’s galleries continue to preserve Earl Biss’s legacy through ongoing collection, exhibition, and interpretation of his work to ensure it lives on for future generations.

Final Years & Lasting Legacy

(1990s–1998)

In the 1990s, Biss focused less on exhibitions and more on creation. He immersed himself in research and travel, continually returning to the canvas with renewed passion. After setting up a studio in Venezuela, he eventually returned to Santa Fe—kissing the ground in gratitude and ready to paint once more.

Though he had struggled with substance abuse, Biss was six months sober and working relentlessly when he suffered a stroke in his Santa Fe studio on October 17, 1998. He passed away the next evening, surrounded by loved ones, at age 51.

The Crow Nation honored him with a traditional burial. Native artists mourned the loss of a trailblazer and brother; collectors lost a visionary; and the art world lost a blazing spirit who will never be replaced.

Much of Biss’s personal story has been preserved thanks to Lisa Gerstner, longtime confidante, director of the documentary Earl Biss: The Spirit Who Walks Among His People, and author of his biography by the same name. Art critic and friend John Goekler captured the depth of Earl’s visual journey in Moving Paint: The Life and Art of Earl Biss, offering a vivid chronicle born from their close friendship.

“See, I believe that there's a reason for being alive, and this reason is this job that I've been given. And it seems like I've lived many times trying to get this same thing accomplished, and I think I'm getting closer and closer to completing my job. And after I complete my job, I feel that I'll be allowed to leave this life into a much more rewarding and peaceful life. And, so I really am glad that my life is nearing its end, because I feel in a way that this is part of a new beginning. It's very difficult to put into words exactly what I'm trying to say.”

— Earl Biss, 1997

“I feel that too many of us have lost touch with the beautiful world that is around us. If I can share with people a dream that is pleasant, I feel that I have fulfilled a responsibility that I must share with my fellow man. I like to think of my painting as windows to another time and place — a magical window through which one's mind may drift: a place that is good and right.

If I had my way the world would be beautiful, alluring, idyllic, simple, poetic and heroic. I know the old days will never be again, but in my dreams I see them.”

— EARL BISS